Why Mass Migration is Not Solution to Ailing Growth in Africa

18 min Read October 18, 2024 at 8:50 AM UTC

Contributed by Timothy Kasuka, publisher of United States of Africa Substack.

Migration in a world where you apply online and then simply hop on a plane

The global migration picture of 2024 and the last 70 years or so has been one of economic migration, mostly from the relatively poorer regions of the southern hemisphere towards those of the richer parts of the northern hemisphere. Countries like the United States, Canada, Germany, France, Australia, South Africa, and my home nation of the United Kingdom pack the lists of those planning to make the leap of location.

In fact, millions upon millions settle into the handful of countries listed above annually, but is movement at such scale sustainable or even really desired, from the perspectives of both the destination and emigre places?

According to some, like the globalists of the day, the aforementioned movement of people is a win-win arrangement for everybody involved: host countries benefit from large-scale immigration by meeting their worker demands in critical industries like healthcare, hospitality, and construction, all the while reaping the rewards tied to the additional spending and economic activity generated by newcomers.

Conversely, the poorer countries that these migrants once called home now essentially have one less mouth to feed, with them adding this person to an increasingly lucrative source of income and foreign exchange in the form of overseas remittances.

Short-term gain for long-term pain

But I don’t see it as a win-win arrangement, or at least not in the long-term. The scale of migration that we’ve witnessed over the last 20 years is actually locking much of the southern hemisphere into a cycle of poverty and dependence, and placing added strain on the resources and infrastructure of the rich world. There has to be a better path to elevated growth and living standards.

Mass migration is nothing more than a band-aid solution to the economic woes felt by nations on either side of the equation. It’s a sub-optimal measure that involves bringing in more people to compete within limited spaces for limited markets as more move from the more populated developing world to the geographically smaller and relatively lightly populated rich world.

A more dynamic and sustainable way forward begins with us exploring how the talents and skills of people in developing regions can be best utilized where they are. I think that this is the optimal solution where heaps of people do not need to leave their families and cultures behind to simply make ends meet in a new environment that’s largely alien to them.

Which country ever got rich off remittances?

The story of China embodies the optimal approach to development and poverty reduction. The Middle Kingdom grew famous for sending Chinese migrants to all corners of the world throughout history. At one point, the Chinese Diaspora ranked as the largest in the world – a title recently taken by the Indian Diaspora.

However, such vast volumes of emigration throughout centuries past did not pay much by way of economic dividends for the country, even if it did for its emigres. Remittances from a large number of wealthy people abroad simply weren’t enough to fix what was a broken economic system.

Only when China took on a form of free market capitalism and opened up its economy to global trade and investment – culminating in its accession into the World Trade Organization in 2001 – that the country was finally able to climb its way out of poverty. And by getting it right at home rather than overseas, China can accumulate wealth and raise living standards in a way that simply isn’t possible for its Diaspora to supplement in any meaningful way. Remittances aren’t going to lift 800 million people out of poverty and add hundreds of millions to the middle class.

The global economy (Africa in particular) is also much better off as a result of the Chinese Economic Miracle. China is the factory of the world and is the second largest importer of its goods and services; the spending power and economic impact of Chinese tourists and students across the West far outweigh that of the Chinese economic migrants in these same places.

Learning from Ireland

A similar case study can be outlined using the example of the Republic of Ireland. Emigration had become a way of life for the Irish ever since the onset of the Potato Famine in 1845. The cultural and ethnic legacy of such massive migration can be seen in the scores of Irish communities and their ancestors found in countries as far as the United States, Australia, the United Kingdom, and even Jamaica.

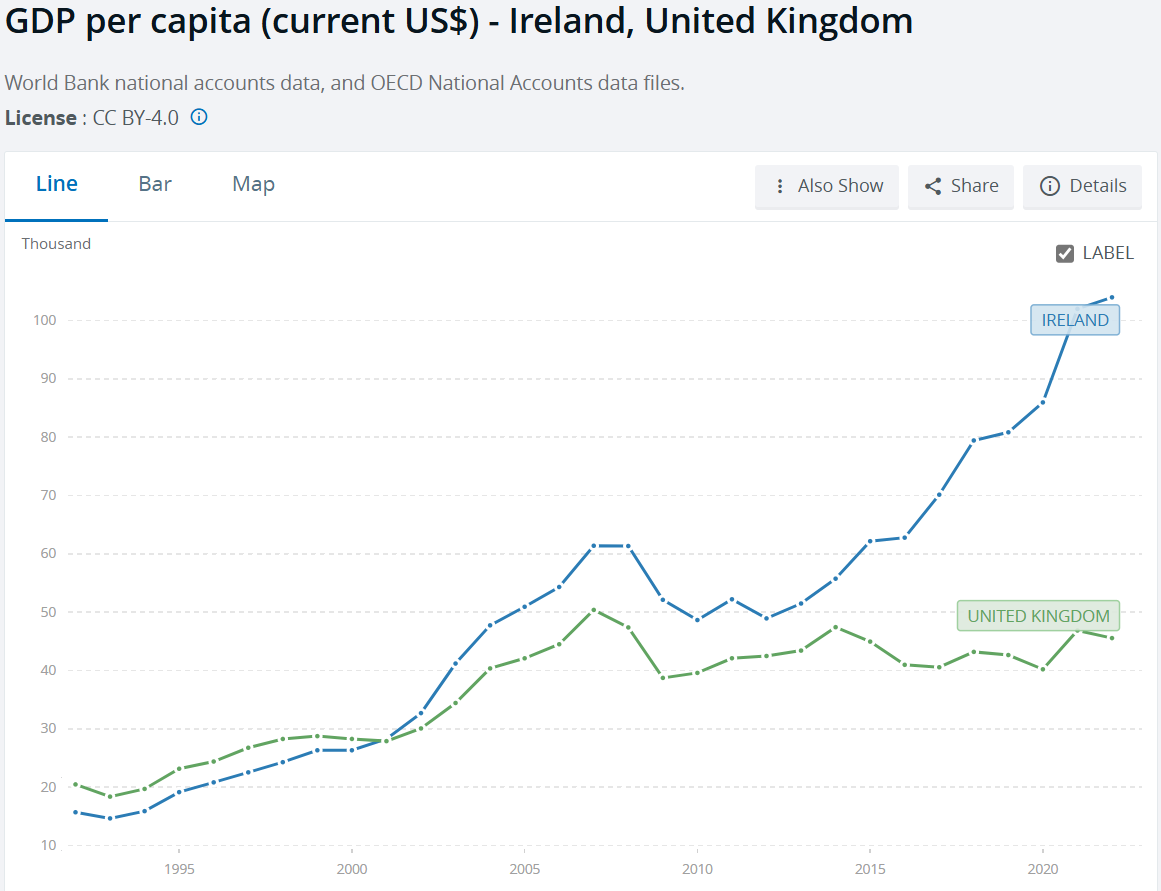

The total number of Irish immigrants and those of Irish descent throughout the globe is estimated at between 50-80 million. A figure that’s at least around ten times that of the population of Ireland today. But, despite an Irish-descended US president like John F. Kennedy belonging to one of the wealthiest families in America at the time of his presidency, Ireland itself was still something of an underachiever when compared with the rest of the United Kingdom and the rest of Europe. Its GDP per capita was 75 percent of the UK’s as recently as 1992.

Yet, 10 years later the Irish Republic’s GDP per capita exceeded that of the UK’s. What changed: were the Irish Diaspora suddenly able to come together and provide major economic stimulus for the country? Not quite, what instead happened was that Ireland adopted the euro currency in 1999. This meant that the country adopted the regional currency of the euro, complementing EU membership and a favourable location nearby a much larger economy in Britain. The Good Friday Agreement between Ireland and the UK in 1998 also helped in creating the conditions necessary for economic take-off.

The Curious Case of the Philippines

Look at the Philippines, their Diaspora is famous the world over. In 2013, over 10 million Filipinos and Filipinas were working overseas, representing 11 percent of the country’s population at the time. Remittance flows to the Philippines in 2023 were recorded at $37 billion, making it the fourth-largest recipient of remittances in the world.

However, remittances don’t seem to be registering much across the country on the development front. The South East Asian nation is still one of the poorest in the region and the whole of Asia, being labelled as a perennial underachiever and the ‘Sick Man of Asia‘ for decades on end.

Economic models that tap into an outlook of abundance, where plans to secure growth opportunities aren’t largely limited to economic sources overseas seem to be delivering. These models prioritize exploiting their homegrown advantages, be that cheap labour and land, language skills, or an advantageous trade and business location, to sell to and attract investment from much bigger markets.

This is why emigration and remittances, no matter how much they continue to grow, will not deliver on development for Africa. We could even argue that they are inhibitions, rather than stimulants of growth for the continent. Hence, the current picture surrounding mass migration from various parts of Africa into different pockets of the world, mostly in Europe and North America, represents a sub-optimal solution to growth for everyone involved.

How mass migration is beginning to hurt host nations:

(i) Foreign labour deployed tends to operate at a relative cost disadvantage

Money spent hiring migrant labour abroad in rich and industrialized countries at much higher wages could go further on a per-dollar basis as an investment in the migrant worker’s home country. The British monthly minimum wage of $2,400 per month could pay for the work of close to a dozen Nigerian full-time workers on average compared to only employing one of them as an employee in the UK.

(ii) Large-scale migration increases the cost of living for the native population

To say this openly is to evoke anger and consternation from some, but I am not too sure why this is the case. The facts are the facts, it’s nothing personal. Houses and apartments are not like loathes of bread that can be churned out the instance a new person arrives in a country. Houses almost anywhere in the world take at least four months to build, and sometimes up to a year or more.

These estimates don’t even factor in the time taken to get the planning permits required to start in the first place. Developers are required to carry out multiple rounds of feasibility studies and consultations with local stakeholders to ensure that developments protect community interests and their quality of life.

Hence, finalizing and approving the planning process alone can take years (even decades in some cases) to complete for buildings planned in the urban centers of the rich world. And it’s these same places (usually consisting of a handful of a nation’s major cities) that attract the lion’s share of incoming migrants, as many naturally flock to these spots to better access good quality schools, general amenities, and job opportunities.

How exactly is a country like the UK, which is already falling behind in meeting the housing demands of the native population, then supposed to muster up the means to accommodate an additional 600,000-700,000 people per year?

Well, the UK and many other places simply don’t since the task in and of itself is Herculean. A recent meta-analysis carried out on eight different countries concluded that “On average, a 1% increase in immigration in a city increases rents by 0.5–1%”. Such an effect also has the potential to offset a dangerous cycle, where less affordable housing reduces family sizes and a nation’s total fertility rate declines as couples have fewer children later. In response, said nation goes back to the wishing well of immigration to retain its worker-to-pensioner ratio (in the short-term), only to exacerbate the spiral.

(iii) More intense levels of migration likely to lead to less culturally harmonious and more ethnically fragmented societies

It can be said that migration is to a country what cinnamon is to a meal: moderate additions spice up dynamics and can lead to healthy developments, but too much of it envelops and eviscerates the essence of the dish. Newcomers bring with them new ideas and perspectives, that generate fusion and innovation. Nonetheless, like anything in life, it has its breaking point.

As migration volumes near closer to a critical mass, clusters of different ethnic communities begin to form and gain momentum. Such heterogeneity of cultures, religions, and histories then begins to tug away at what a society might have once identified as a collective memory, common values, customs, and quirks. Trust between inhabitants begins to break down and people segregate off and seek security within their own blocs. Blocs that they now have a vested interest in preserving and expanding.

Why it’s bad for Africa and other developing regions:

(i) Brain drain, brain drain, and more brain drain

Anyone with a cursory understanding of African affairs – with this applying to many Africans themselves – is very much aware of the adverse impacts that the departure of a large number of its sons and daughters of the soil has on the continent. Culturally and spiritually, the communities and countries that migrants once called home begin to stagnate – they experience brain drain. So systemic flaws and distortions become entrenched as many of those who may have been best placed to shake things up and deliver change are now gone.

It’ll be difficult for a country to make any progress on the healthcare front for instance, if a significant share of their best doctors and nurses keep on moving on for supposedly greener pastures overseas. How can a country like Nigeria for example, expect to achieve any real advances in research, training and health outcomes if nearly half of their already highly scarce doctors are not currently practicing in the country?

Data also suggests that the adverse economic consequences for countries exporting so many of their skilled workers can also be steep. A report published by the Pollution Research Group in the early 2000s estimated that it was costing Africa $4 billion a year to replace its outgoing skilled professionals with Western expatriate workers.

This number also doesn’t account for the resources plowed into training and preparing skilled African emigrant workers earlier on in their lives by the country in the form of taxpayer money and manpower. Another more recent study found that the cost to a country subject to a large-scale exit of homegrown doctors can be anywhere between $3.5 billion and $38 billion annually once we consider the excess deaths offset by the resulting shortages.

(ii) Financial remittances might unknowingly increase inequality

Remittances can also contribute to widening a nation’s divide between the rich and the poor. Those with the connections, skills, and wherewithal to finance travel abroad and land a job tend to come from the more affluent segments of society. Upon migrating overseas and sending money and gifts back home to family and friends, the difference in the financial prospects between those with connections outside of the country compared to those without becomes more pronounced. This reality also feeds into increasing the allure of an escape abroad, perpetuating the broader problem.

Furthermore, for recipient nations that lack many reliable vehicles for protecting and accumulating wealth, as is often the case in lots of countries across Africa and the rest of the developing world, remittances can become inflationary. People are likely to direct some of the remittance proceeds towards financing land and property purchases. Subsequently pushing up land values and driving up rents for everyone else – or the overwhelming majority who own very little valuable land.

(iii) How important are remittances to economic growth?

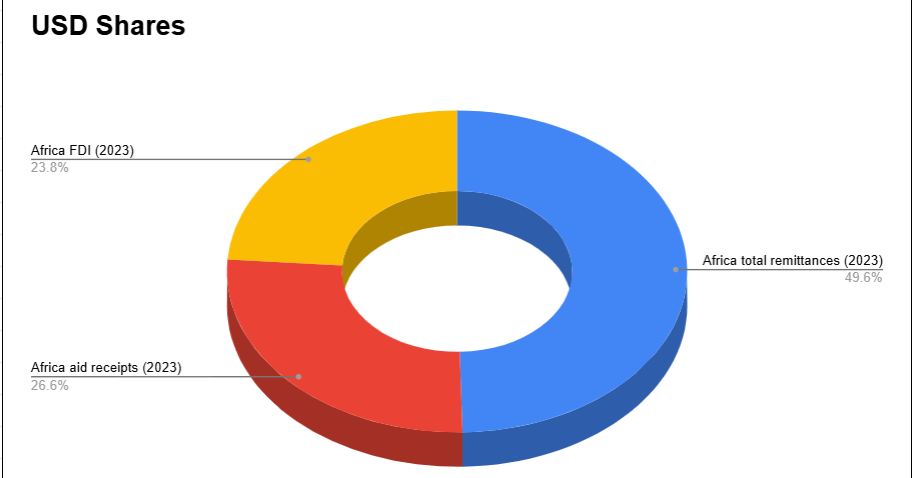

At about $100 billion per annum, remittance flows into the continent of Africa and the sum of its international aid and foreign direct investment are neck-to-neck in scale.

Yet, over time, as remittances to Africa have grown in size and intensity as the scale of the diaspora continues to increase, growth at home remains subpar. In fact, in 2020 a group of researchers conducted the first meta-analysis of 95 different studies examining the relationship between remittances and economic growth. All in all, it found that the mean effect on growth was positive but small. What is more, the analysis highlighted how remittances seem to aid growth in Asia but not Africa.

This makes sense once you look at how many African nations are structured economically. Many lack the industrial base to produce a lot of goods locally, so a lot of whatever money that is received from overseas goes right back out in the form of imports. As noted in the study, since remittances mean larger volumes of dollars being exchanged for different national currencies, this tends to lead to an appreciation in the value of local currencies, possibly contributing to deindustrialization as African manufacturers become less price competitive at home and abroad as well.

The sickness is in the system, and remittances are usually expended on merely keeping its participants above water, by helping friends and families meet immediate consumption needs like accessing food and electricity or paying off school fees. If Africa is the patient then remittances are the treatment, not going far enough to address the problematic interactions and behaviors that give rise to the continent’s ailments in the first place.

In economic terms, money sent back home helps Africa to meet its consumption needs, but does little in boosting its production needs. This could be changed by countries exploring ways to guide remittances to local industries through investment vehicles such as corporate bonds and the stock markets as I have written about here.

Africa needs moderate levels of immigration, not crippling levels of emigration

I would also like to use this article to proffer a policy solution for Africa rarely considered in development circles: the targeted migration of skilled workers into the continent. Many of Africa’s leading economies, like Kenya, Mauritius, South Africa, the Ivory Coast and Botswana, also happen to host relatively vast and diverse immigrant communities.

Be it historically or in the present, the positive effects are long-lasting. The migrants coming into these nations can apply their industrial and technical expertise in new settings to unlock growth and expansion. For instance, one of the largest manufacturers in Nigeria and probably Africa just happens to be operated by the Lee Group, a Chinese-owned industrial conglomerate that first set up shop in the country way back in the 1960s. The company employs more than 25,000 workers in 50 locations, working to facilitate skills, knowledge, and technology transfers throughout Nigeria.

The presence of Lebanese and Indian communities within Africa has also contributed to expanding the continent’s industrial capacity. Mauritius is home to a large contingent of Asian Mauritians and a broader, more transient international crowd, enabling the country to move up the economic ladder and become one of the wealthiest countries in Africa on a per-capita basis.

I would also like to stress that the benefits accrued by this economic transformation are not limited to these communities with foreign connections, as many may perceive them to be at first sight. Africans on the mainland have the option of moving to Mauritius to share in its economic opportunities. Major African corporations like the Afrieximbank and Sanlam Holdings, have tapped into Mauritian equity markets (the ninth largest in the whole of Africa) to finance expansion. Mauritian companies themselves also invest in economies throughout Africa while serving as a convenient point of entry for foreign firms (particularly those from India) looking to break into the continent.

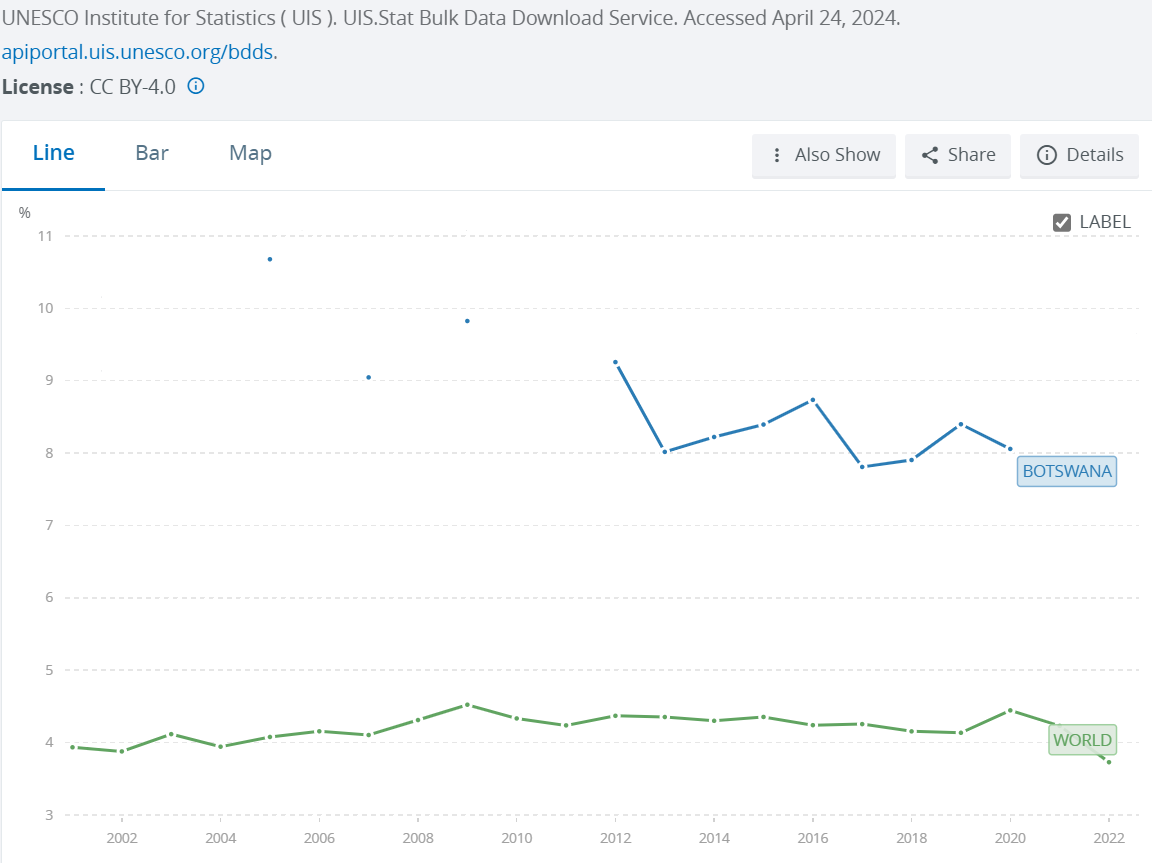

An African nation with Western rates of net migration

Botswana serves as another great example of how migration into an African country can be beneficial for the host nation. Recent figures show that Botswana had a net migration rate of 6.51 per 1,000 persons, double that of the USA’s 3.28 per 1,000 persons (in terms of legal migration) and about two-thirds of that of the UK’s 10 per 1,000 persons in 2023. By many counts, Botswana boasts one of the highest net migration rates across the continent as a whole and is one of the few that records net migration rather than net emigration.

” Foreign workers were aggressively pursued to fill skills gaps in sectors including technology, management, education, engineering, law, and healthcare, and were offered competitive salaries, subsidized housing, cars, health insurance, and free education for expatriate children.”

This is by no accident, according to the Migration Policy Institute, for Botswana, ” Foreign workers were aggressively pursued to fill skills gaps in sectors including technology, management, education, engineering, law, and healthcare, and were offered competitive salaries, subsidized housing, cars, health insurance, and free education for expatriate children.” As a result, the number of foreign residents based in Botswana more than doubled to 60,000 in 2001 (3.4 percent of the population at that time) from 29,000 in 1991. At the same time, the government aggressively invested in educating and training its workers, with recent figures on government spending on education for Botswana being between 8 and 10 percent of GDP or about double the global average.

Not only did they prepare their youth in the classroom, but Botswana also structured the workplace in a manner that would enable the transfer of key skills, best practices, and highly prized tacit knowledge from the nation’s expat workers to the local workforce. It did so by requiring companies to take on Batswana ‘understudies’ of sorts, who were trained and groomed to eventually take on the skilled positions held by foreign nationals at the time. Such a policy is not uncommon across many parts of the world.

Indeed, I first learned of this practice from a friend who worked for the Tesco Shanghai office during my second visit to China as an intern in 2011. The arrangement pays dividends for both the country and the company, with one party gaining an extra skilled worker over time, and the other party eventually being able to hire a local to carry out the job of the foreign worker at more competitive pay.

Mass migration in an age of cheap and fast travel will simply unravel

Mass migration is a sub-optimal solution to global economic challenges, much like pouring more water into an already crowded reservoir—it increases strain without addressing the root issues. While remittances provide short-term relief, they fail to solve the deeper economic problems faced by developing nations. The optimal path lies in empowering people to succeed where they are, by strengthening local industries, investing in talent, and fostering sustainable growth at home. This approach alleviates pressure on host nations while offering a more lasting, resilient solution for global development.

This article was first published in the United States of Africa on Substack.

This material has been presented for informational and educational purposes only. The views expressed in the articles above are generalized and may not be appropriate for all investors. The information contained in this article should not be construed as, and may not be used in connection with, an offer to sell, or a solicitation of an offer to buy or hold, an interest in any security or investment product. There is no guarantee that past performance will recur or result in a positive outcome. Carefully consider your financial situation, including investment objective, time horizon, risk tolerance, and fees prior to making any investment decisions. No level of diversification or asset allocation can ensure profits or guarantee against losses. Articles do not reflect the views of DABA ADVISORS LLC and do not provide investment advice to Daba’s clients. Daba is not engaged in rendering tax, legal or accounting advice. Please consult a qualified professional for this type of service.

Next Frontier

Stay up to date on major news and events in African markets. Delivered weekly.

Pulse54

UDeep-dives into what’s old and new in Africa’s investment landscape. Delivered twice monthly.

Events

Sign up to stay informed about our regular webinars, product launches, and exhibitions.